Chapter 8, Developing Running Speed and Agility Skills, contains everything you need to know about development, skill focus, practice, drills and sport-specific training. Clive breaks down the biomechanics of the body, how it maneuvers, and how to optimize speed and agility based on sport and experience. I had to review this chapter three times to try and figure out a way to simplify Clive Brewer’s words in a blog! It’s a tough task because it’s so perfect, but I will do my best. I’m going to highlight three key points that really spoke to me about how to utilize speed and agility effectively.

Chapter 8, Developing Running Speed and Agility Skills, contains everything you need to know about development, skill focus, practice, drills and sport-specific training. Clive breaks down the biomechanics of the body, how it maneuvers, and how to optimize speed and agility based on sport and experience. I had to review this chapter three times to try and figure out a way to simplify Clive Brewer’s words in a blog! It’s a tough task because it’s so perfect, but I will do my best. I’m going to highlight three key points that really spoke to me about how to utilize speed and agility effectively.

First, I want to quote Clive on p. 169 when he said,

“To understand movement speed and agility, the practitioner must understand not only the athlete’s technique but also the objectives of the skill being exhibited.”

Clive is referencing biomechanics of speed and agility and how to relate this to the athletes’ sport.

In order to be effective in a sport the athlete needs to understand the mechanics of the sport. In most sports, speed and agility plays a part in how successful the athlete will be. For example, let’s take the game of basketball. This sport requires locomotive skills and postural control to help stabilize during acceleration and deceleration while dribbling and running up and down the court. An athlete who plays basketball wouldn’t be too concerned with maximum velocity, but instead optimal velocity to allow for maximum mobility in the musculature as a function of joint positioning. An athlete with biomechanics-based training drills and practice (and good overall health) will consistently perform better. For the game of basketball, it’s about optimizing and honing one’s skill for the game. I wouldn’t train a 100-meter sprinter and basketball player the same way. Why? Think about the goals of a sprinter compared to those of a basketball player. In a sprinter, I would try to maximize the highest velocity, speed and technique to train explosiveness. On the other hand, with a basketball player, speed and agility training needs to focus more optimization, endurance, and change of direction.

Second, after discussing the biomechanics of the athlete and the importance of sport specific training, I want to touch on how to develop technique for running.

The basis to understanding running is the correlation between stride length and velocity.

A common misconception is that taking longer strides covers more ground, which leads athletes to be faster. What this line of thinking overlooks is that the foot to ground contact time is too long, meaning it will take longer to accelerate. But remember, training should be based on the goals of the sport and athlete; long distance runners utilize submaximal intensity as opposed to explosive speed. They may require longer strides to cover ground and conserve energy. A 100-meter sprinter does require explosive movement, so stride length must be optimized to produce faster acceleration. A common discussion in running is the technique regarding which parts of the foot contact the ground at certain points. I learned something new about that: the heel to toe running technique is used in order to conserve energy and absorb the ground reaction force. I was taught to run “on the balls of my feet,” which allowed me to move faster. But I’m sure if I had to train for long distance, I would incorporate the “heel-to-toe” method; because it will allow me to make more foot to ground contact without exhausting myself.

The other important technique that we cannot ignore are the arms. What do you do with them!? Well, the rule is opposite arm to forward leg. When the arms and legs are not in sync, it appears awkward and ineffective, any typically causes the hips to rotate. The same thing occurs when trying to run with the arms coming across the body when running. It’ll slow you down; the arms need to stay by your side, moving fast, and short arm movement throughout, 90 degrees.

One last thing to remember when running is knee and ankle movement. A common mistake made by young athletes is pointing the toe towards the floor. When this happens, the muscles that help accelerate the body are likely to be inhibited (gluteus maximus and calf muscle). Instead, the knee should drive forward when the leg moves forward, the ankle should be dorsiflexed, allowing the knee to pull forward toward the toes. Important Note: the closer the ankle is to the buttocks, the greater the running speed will be; it allows for rapid rotation underneath the body. Based on my personal experience, if your goal is to increase max speed, work on form and technique, it will greatly increase top speed!

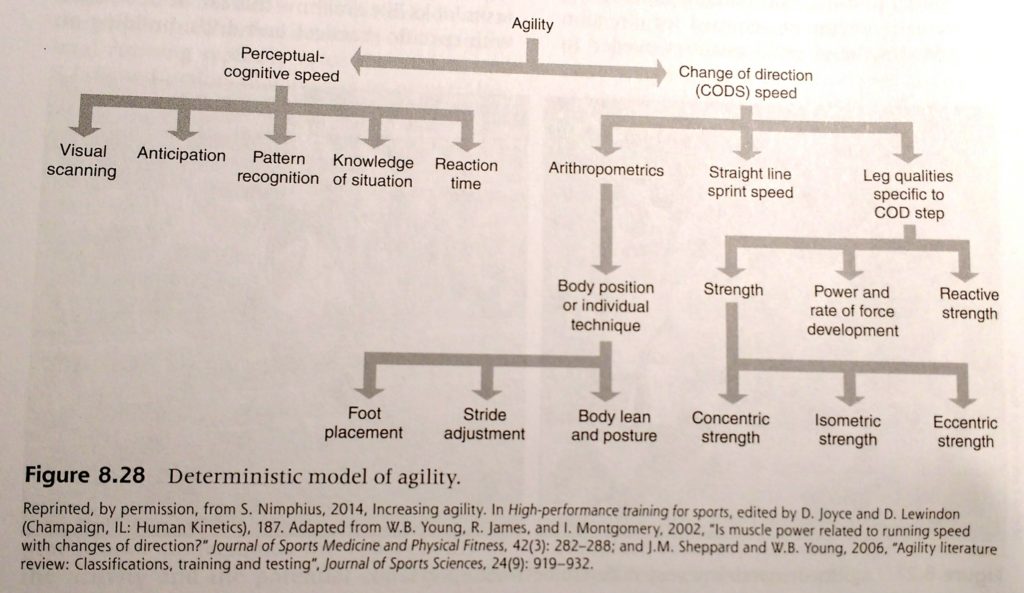

Thirdly, agility is the physical attribute that taps into the athlete’s motor and cognitive ability. Agility is in itself considered sport specific training, but it also must be specialized to the demands of the sport. Most professionals know that there are a variety of agility drills. Let’s say the trainer decides to train the athlete in every format and the sport is tennis; the athlete will never be able to optimize the specifications required for that sport he/or she is training for. I believe that to maximize the performance results of an athlete, their agility training needs to correlate with their specific sport. Tennis deals with a lot of change of direction movement, requiring quick reaction times. This is developed through practice and making those neuromuscular connections. Clive Brewer mentions on page 210, third paragraph,

“Recent research indicates that, although most sport performers need the ability to accelerate to maximal speeds in a range of time frames, linear speed and directional change ability are not highly correlated. Therefore, training for change of direction speed and agility must involve highly specific training that develops directional change skills that can be incorporated into the specific demands of the sport.”

On the page, he showcases a great deterministic model of agility. Below is a similar graph related to the book.

Thus, when referencing agility, think about the reaction time during the change of direction, this is the basis for agility development. Progressing to the next stage would be enhancing the perceptual and decision making skills. Clive mentions a game of cat and mouse, basically a game of tag, 1:4 ratio cat to mouse. When tagged the mouse is frozen, he/or she can be unfrozen when another mouse makes one circle around them, two times for advanced people; duration is 1-3 minutes before resting. Games are great for young children to understand how to improve direction, both strategically and physically.

This chapter provides much more insight into speed and agility than I have covered. But these three topics stood out to me:

-

the biomechanics of speed and agility,

-

developing technique for running, and

-

the importance of specializing agility.

I will utilize what I have learned in my own training, as well as my client-athlete training programs. Some key points to remember from this blog are to work on technique to build speed and agility, determine what you are trying to achieve through training, and then determine how to optimize speed and agility in your programming. After, reading this blog, what are some points you can utilize in your own training? How are you going to incorporate this into your own programming?

Did you like the ideas presented in this blog? If so, please add a comment below for Coach Cowick. Our team of bloggers would like to get your feedback. When you submit a comment our goal is to re-post it within 24 hours. Thanks!

Personal Trainer at Fitness Connection and Camp Gladiator

“The views, opinions, and judgments expressed in this message are solely those of the authors and peer reviewers. The contents have been reviewed by a team of contributors but not approved by any other outside entity including the Roman Catholic Diocese of Raleigh.”