Body Archetypes and the Tunnel by Erin Blaser

Coaches and athletes may be able to relate to the “crossed wires situation,” (i.e. the situation of not being able to effectively communicate with one another.) The coach instructs the athlete to flatten their back during a deadlift, and they drop their shoulders, creating a rounded position instead. I personally have tapped dowels to my clients’ torsos in order to train the flat back of a hip hinge, and have seen other trainers who have had to physically move their clients’ limbs, and push and pull them into proper positions for exercises. It is a situation of simultaneous humor and frustration. Wouldn’t training be more effective if everyone just understood how their bodies need to be positioned and were able to do it?

This chapter on archetypes that I’m covering in this blog post does not offer a direct solution to this issue, however it does shed light on what the ideal positions are for the hip and shoulder girdles, and provides some great tips on how to use them to make coaching more effective. In this blog I will first discuss the seven “archetypes” (as Starrett calls them): what they look like and how to test them; and then I will talk more about how to apply these positions to coaching.

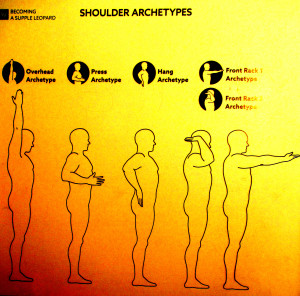

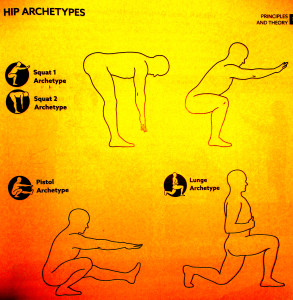

According to Starrett there are seven body archetypes: four for the shoulder girdle, and three for the hips. These archetypes are ideal positions, that “represent the stable positions for the hips and shoulders, and encompass the entire range of motion for most shoulder and hip movements” (Starrett, 115). They exemplify common movement patterns that are not only used in the weight room, but also in activities of daily life.

(Starrett, Page. 92)

1. (Shoulder) Overhead

What it looks like: shoulder in full flexion (biceps behind ears) with elbows locked out and thumbs pointing backward (armpits forward). The spine and neck should be in a neutral position.

Common associated movements: reaching/pressing overhead, hanging, throwing

Common associated exercises: pull up, overhead squat, snatch, jerk

2. (Shoulder) Press

What it looks like: shoulder extended so the elbow is behind the ribcage. The elbow is bent so that the forearm is parallel to the floor and palm is down. The spine and neck should be in a neutral position.

Common associated movements: reaching behind you, jumping, getting off the ground from your belly

Common associated exercises: push up, dip, row, burpee

3. (Shoulder) Hang

What it looks like: shoulder extended so the elbow is behind the body at chest height. The elbow is bent so that the forearm is perpendicular to the floor and palm is facing back. The spine and neck should be in a neutral position.

Common associated movements: standing with your hands at your sides or in your pockets, carrying a load on your back

Common associated exercises: deadlift, clean and snatch set up

4. (Shoulder) Front Rack

What it looks like: shoulder in flexion so the elbow is shoulder height. There are two different variations on this position: one with the arms straight and palms toward the ceiling; and the second with the elbows flexed and palms facing upward. The spine and neck should be in a neutral position for both.

Common associated movements: reaching behind you, jumping, getting off the ground from your belly

Common associated exercises: push up, dip, row, burpee

(Starrett, Page 93)

5. (Hip) Squat

What it looks like: Hip flexion and external rotation. There are two different variations on this position: one with the knees and feet outside the shoulders, and the hips sitting below the knee crease; and the second with the knees extended, shins perpendicular to the ground, and back flat. The spine and neck should be in a neutral position for both.

Common associated movements: getting into and out of a chair, bending over, lifting something off of the ground

Common associated exercises: squat; jumping and landing; clean, snatch, and deadlift set up

6. (Hip) Pistol

What it looks like: Hip, knee, and ankle flexion. This is a single leg position, with one leg extended out in front of the body while the other is completely bent at the knee and hip joints (so it looks like someone is sitting on their heel). Proper form includes a stable ankle, the bent knee in line with the foot, and a neutral upper back (arms are typically held out in front of the upper body).

Common associated movements: getting up off the ground from a seated position, stepping up onto or off of an elevated platform

Common associated exercises: pistol squat

7. (Hip) Lunge

What it looks like: Hip extension and internal rotation. Lunge position with the back leg with 70-90° of flexion and the knee behind the hip; and the front leg with a vertical shin and knee aligned with the foot.

Common associated movements: running, walking up stairs, climbing uphill, kneeling

Common associated exercises: split jerk, lunge

In order to test each of these archetypes on an athlete or client, simply use your best coaching cues to describe each position. As with all assessments, the goal is to see how the person interprets the concept of the motion, not to see how well they can follow directions. In order to get the most preferable result and to best understand how the athlete/client interprets movement, it is better to coach less in your instruction. For example, to assess a client’s lunge position, instructions would be closer to “stand hip-width apart and take a big step forward, bending both knees until your back knee lightly touches the floor,” than what is in this post for what the proper lunge position looks like. Some tweaks may need to be made here and there, but the goal is to grasp the athlete/client’s current state; the correcting and coaching comes later.

Assessment of clients and athletes on their positioning in each archetype can provide a significant amount of insight into their muscular imbalances and limitations in mobility. Starrett advises taking the information gained from such assessments to address mobility issues primarily; however, that advice may not fall under the scope of practice of a personal trainer or a strength coach. What does fall under our scope of practice is coaching proper technique. Poor positioning can be corrected by good external cueing, and technique must be assessed in every lift, whether it is a body weight squat or a max deadlift.

Let’s talk a little bit more about the application of Starrett’s archetypes to coaching. You may have noticed in the listings of exercises that were associated with each archetype some were the actual name of the position, and some exercises also included “set ups.” Early in this chapter, Starrett introduces the tunnel concept: one must begin a movement (enter the tunnel) in a good position in order to finish the movement (exit the tunnel) in a good position. The set up for exercises is key to the quality of the movement performed. Think about it this way: it’s much more difficult to get into a “good position” once load, speed, or tension is added into the equation. Try unracking the barbell before bracing your core; it won’t be as easy to obtain that optimal positioning and back stabilization with weight compressing your vertebral discs.

The set up is paramount, but every coach also knows that a lift is no good unless it is finished properly. Starrett makes coaching easier by providing seven ideal start and/or end positions for basic lifts. Teach your athletes or clients to master these archetypes, and the transition from the overhead position to the front rack position while hanging from a bar becomes a pull up. Each archetype can be used as a coaching cue to aid athletes or clients in performing exercises safely and functionally. There is more transitioning between the shoulder archetypes than between the hip archetypes, but even so, these learned positions are great reference points (“position yourself behind the bar in a squat with your hips low and spine in neutral” as a cue for setting up for a deadlift, snatch, or clean).

Starrett’s chapter on Body Archetypes does a great job of breaking down important positions that can have serious implications on the quality of a person’s movement. Coming from a more therapeutic standpoint, Starrett promotes good mobility practice for daily life and safe exercise. As coaches and trainers, we can expand on this idea and use it as a guide to instruct proper movement. It’s definitely a challenge to teach an old dog new tricks, and many clients or athletes that come into our facilities have years of poor movement patterns and positioning under their belt. But this challenge is not impossible; it simply requires time, energy, and practice to reteach this positioning and improve the overall quality of movement (and of life!) of the people we serve.

I recently was at the East Tennessee State University Coaches College, and one of the speakers mentioned that as strength coaches, we do not train [insert sport here] in the weight room. We make athletes stronger so that they can go out and play their sport better. I could not agree more; we work to strengthen the rotator cuffs of swimmers and baseball pitchers, but do not coach the angle that the arm must hit the water or the follow through on a curve ball. However, helping athletes gain strength in the most stable positions will transfer to how stable they are in similar positions during sport. A hurdler that exhibits knee valgus (toward the midline) during a basic or loaded lunge is more likely to have inconsistent ground contact and force production during running, which could cause complications when they try to launch themselves over an obstacle.

As a personal trainer who works with clientele displaying a myriad of health issues, muscular imbalances and tightness, and coordination and balance issues, I am very excited to implement Starrett’s archetypes into my training. Many of my clients are new to strength training, and are open to learning the proper ways to move and position themselves so that they will avoid injury. I can see how these positions transfer to daily life activities and know that everyone can benefit from improved quality of movement. I also am excited to develop a coaching vocabulary with the people that I train. After building a base with Starrett’s archetypes, clients can learn more complex movements through association. Being able to use movements that they are familiar with and have ingrained in their brains will hopefully lead to less “crossed wires” and more efficient workouts!

Erin Blaser, NASM CPT 12/22/2015

Resources Cited:

Starrett, Kelly, with Glen Cordoza (2015) Becoming a Supple Leopard. Victory Belt Publishing Inc, Las Vegas: Second Edition. (pg. 92, 93, 115).

“The views, opinions, and judgments expressed in this message are solely those of the authors and peer reviewers. The contents have been reviewed by a team of contributors but not approved by any other outside entity including the Roman Catholic Diocese of Raleigh.”

“The views, opinions, and judgments expressed in this message are solely those of the authors and peer reviewers. The contents have been reviewed by a team of contributors but not approved by any other outside entity including the Roman Catholic Diocese of Raleigh.”