I want to start by reminding us all of the “why we do what we do” so that we have a clear destination for this blog. To do so, I am going to ask a simple question…

What is the goal of training?

I would say (and I think most would agree) that the goal of training is to achieve adaptation. We want to achieve structural and functional adaptations that come from training specific energy systems (see last week’s blog by Erin Blazer), specific movements, specific volumes and intensities, as well as other things that all work together to increase an athlete’s ability to perform. Tudor Bompa, author of “Periodization Training for Athletes” dedicates a whole chapter to emphasize the role of fatigue and recovery on achieving training induced adaptions.

Fatigue is complex, encompassing physiological and psychological factors, and its results are multi-faceted. Looking at the Central Nervous System (CNS), we have learned that CNS sends impulses to the working muscle cell to cause contraction by regulating the number of motor units recruited (and type), the frequency, and ultimately the contraction force. In order to protect the muscle from sustaining too much damage, the CNS will eventually inhibit the signals sent to the muscle, thus inducing a decrease in contraction (performance). During intense activities where oxygen is limited, the lactic system begins using muscle glycogen to produce ATP. Eventually, Hydrogen ions and Lactate begin to accumulate in the cells causing a state of acidosis (pH levels decrease). Acidosis inhibits calcium from binding to troponin, which in turn means the signal for the muscle to contract is blocked. It is important to note that the lactic acid is partially responsible for the onset of fatigue during high-intensity bouts, but is not responsible for muscle soreness. It is a myth the soreness is a build-up of lactic acid because lactate is removed from cells fairly quickly and converted back to glucose by the liver. Muscle soreness is essentially the result of damage to the muscle fiber and its contractile units.

So, what does fatigue look like across different activities?

- Speed and Power Sports – slower reactions and decrease in coordination. (Fast Twitch fibers are more susceptible to fatigue).

- “short rest intervals (the standard 1-2 minutes) between sets of maximal neural load are insufficient to relax and regenerate the neuromuscular system to produce high activation in subsequent sets.”

- Eccentric actions place more tension on muscle, activate more fast-twitch motor units, and generate more heat. These reasons explain why eccentric actions lead to greater soreness.

- In medium and long duration events, the availability of oxygen is paramount to success. As oxygen becomes insufficient there is usually a gradual breakdown in technique and a gradual decrease in speed of the movement.

The best way to reach our goals and protect against fatigue is to prevent the accumulation of fatigue by programming adequate rest and making sure to take advantage of quality recovery strategies.

“Without proper rest, relaxation, and recovery, the athlete coasts into a state of chronic fatigue and poor motivation (signs of overtraining)”

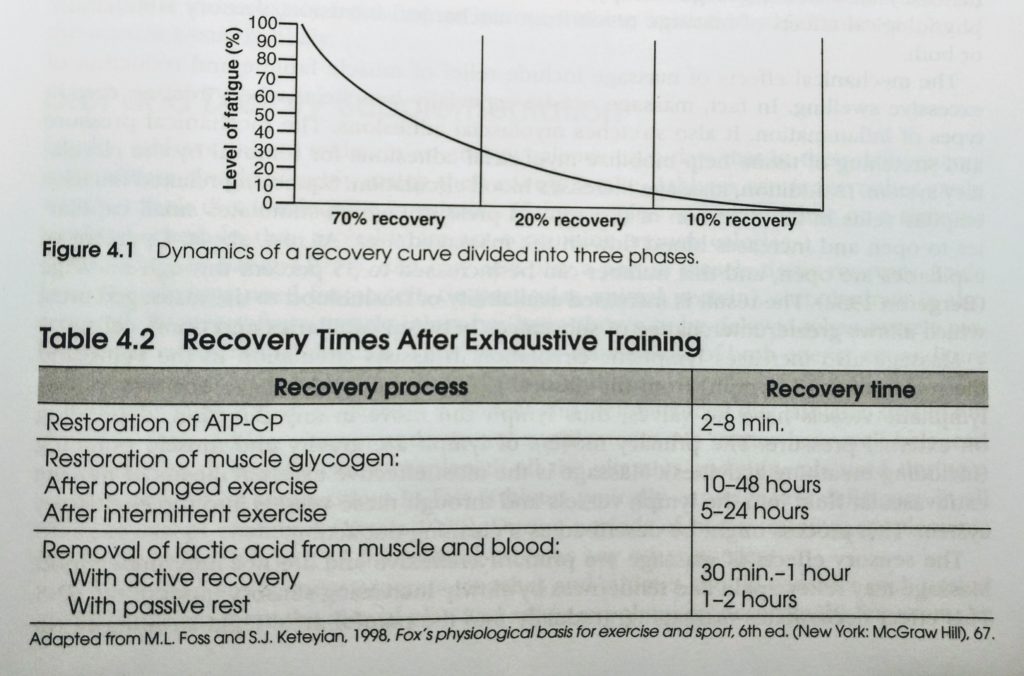

As you look through the following table ask yourself what type of athlete you are training, what energy system are you training, and are you programming adequate rest/recovery to get the most out of their training?

The time interval for recovery depends on the energy system being taxed.

Some things to keep in mind for recovery/rest are:

- to program adequate rest between sets

- ensure the athletes are getting enough sleep (Bompa recommends 10 hours!)

- perform light aerobic activity after a session (active recovery) to remove lactate quicker

- stretch (passive partner stretches) after a session to restore the muscle to resting length quicker.

- massage (to stimulate blood flow to specific areas and stretch out myofascial adhesions.

- Alternating hot and cold during a shower (30 to 60 seconds of each for about 3 sets).

- Talk with your athletes and monitor heart rates before training sessions.

- Proper Nutrition (more on this topic next week!)

This chapter covers a lot but the bottom line is this, “For adaptation to occur training programs must intersperse work periods with rest…” Adaptation is the goal and it is not possible without adequate rest. It is imperative for trainers, coaches, and athletes to understand that “Sometimes less is more, and sometimes rest has stronger effect on adaptation than training does.”

K. Hunter Byrd, NASM-CPT

Research Assistant | UNC-Chapel Hill

Injury Prevention Research Center

Rockin’ Refuel BOGO Special! November 15-29!

Buy One Case, Get One FREE! $18 for TWO Cases (24 units)

Contact coach@morlandstrength.com to purchase

“The views, opinions, and judgments expressed in this message are solely those of the authors and peer reviewers. This content has been reviewed by a team of contributors but not approved by any other outside entity including the Roman Catholic Diocese of Raleigh.”