In coaching, training, and playing sports we often look at the age and size of the athletes, but often we can forget what goes on with development; as a result, factors like training age (how many years of development and practice) and biological age (as girls grow faster than boys) can be minimized along with chronological age (age in years).

Clive Brewer addresses this topic in the third chapter of the book “Athletic Movement Skills” with regards to patterns of motor skill development which is the science discipline concerned with age-related changes. Motors skill patterns are some of the underlying processes that drive appropriate progressions and long-term developments (LTD). The changes in movement pattern tend to occur in a series of stages: childhood (ages 0-5), late childhood (ages 6-9), early adolescence (9 to 12), and adolescence (12 to adulthood). Each developmental stages has different results with the growth patterns in the brain and muscles, and the steps can be drastic from one stage to another. I will be addressing each development state briefly and how simple facts about motor system development need to be considered for each age.

- Childhood (ages 0-5): Movement in childhood does not need programmed coaching, rather, it is an opportunity to develop foundational movement patterns. Moreover, love of physical activity must be a target in this phase thus allowing the children to attain rudimentary aspects of body movements and understanding. “The key is to keep children 100% engaged and 100% active 100% of the time!” Coach Brewer shows that the focus should be on the children developing key energy systems, movement manipulation skills, locomotive control and stability. Thus, the focus should be on just running instead of running to a finish line, how far a kid can kick the ball instead of hitting a target with accuracy, and being able to see how to stop and restart multiple times. This all helps the motor system attain better trainability later in development stages, and allow strength to accumulate later in childhood.

- Late childhood (5 to 9): The brain starts allowing development of finer control patterns, thus formalized practice with specific play activities should be introduced. Agility drills with change in direction can take more important role, balance in more situations can help finer motor pathways, and finally coordination goals and tasks to elect usage of the basic motor patterns.

- Early Adolescence (9-12): This stage is commonly known as the early sport specialization, but the focus here should be on hours and hours of practice than just one skill development. We need to be aware of the development in the early adolescent, as larger muscles tend to take over the movement predominantly as the brain connects to these muscles faster and leaves the finer skill movements behind. Consequently, emphasis should be placed on proper movement patterns like landing correctly, squatting, hip hinging, turning safely, mastering deceleration first, then learning how to accelerate safely.

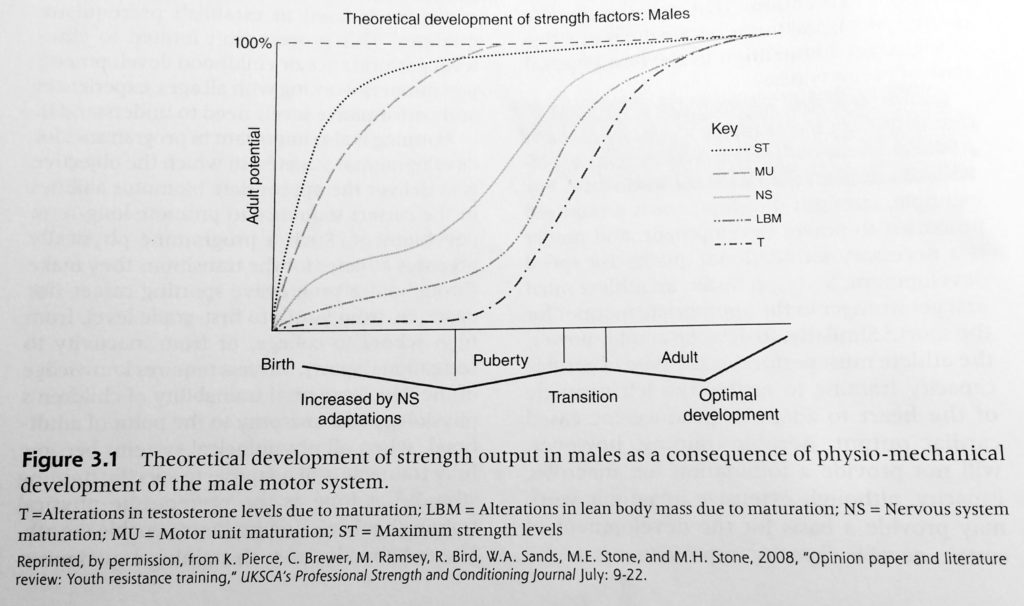

- Adolescence (12-almost adulthood): This is the most important stages in motor system development and athletic preparation, and we coaches can fully utilize this stage in athletes’ lives to create a great impact. Athletes are reaching their peak height velocity (usually earlier in girls in early adolescence), as puberty is allowing many aspects to happen: hyperplasia, cross-sectional area growth, anabolic hormones amount, neurological and morphological strength training benefits are becoming evident. Specialization can be beneficial; however, proper planning to use stacked training aspects must be carefully considered: strength training before power, aerobic activity before anaerobic development, muscular endurance before power endurance. Programming and planning are an important process as Bomba and Haff explain they are key parts of motor system development.

This is a great FIGURE to understand the stages of maturation throughout development!

Coach Brewer states “the athlete’s training age determines whether he or she is ready to undertake such activity, especially with regard to high-volume work.” (Brewer, pg. 35)

In conclusion, in the childhood life stages, changes develop from execution of simple (though coordinated) movements to highly organized and complex movements. In the later life stages of early adolescence through adulthood, changes reflect adaptations to physical aging and disease onset. Each developmental phase can be affected by factors of age, training, motor system maturation and proper progression throughout life. To simply ignore the previous experience of each stage of an individual is to misalign and misunderstand proper planning and progression for any client or athlete.

Amer Nahhas CSCS, NSCA-CPT, USAW-L1

I invite you to invite others to #JoinTheMovement toward better #AthleticMovementSkills! Our team including Coach Amer, Coach Cowick, Coach Blaser, and Coach Byrd, is ready for you to make your move!

Would you like to follow Morland STRENGTH’s link here: new Instagram account?

#MorlandSTRENGTH #AthleticMovementSkills #JoinTheMovement

“The views, opinions, and judgments expressed in this message are solely those of the authors and peer reviewers. This content has been reviewed by a team of contributors but not approved by any other outside entity including the Roman Catholic Diocese of Raleigh.”

Very educational! I enjoyed the read and understood the development goals based on their stage in life. I would like to see in the future, perhaps some real life examples that can be performed based on that stage. But overall, great read!